The War Guilt Clause in Article 231 in Part 8 in the Treaty of Versailles, was by far the most controversial section of the peace agreement. The article demanded that Germany alone accept full responsibility for the losses and damages the Allied nations had sustained during World War I. In 1921, the total cost of the reparations was assessed at $33 billion (equivalent to about US $442 billion in 2018). Furthermore, the Allies insisted that the treaty permit them to take punitive actions if Germany fell behind in its payments.

German reaction to the War Guilt Clause

The harsh terms of the Treaty of Versailles fostered deep resentment in Germany. In October 1918, when the German Government had asked U.S. President Woodrow Wilson to arrange a general armistice, it had also agreed to the Fourteen Points of the postwar peace settlement as formulated by Wilson. However, when the Treaty of Versailles was ready for signature, Germany was shocked to find that the terms of reparation were much harsher than Wilson’s Fourteen Points. In particular, Germans took offense to the provision that blamed their country for starting the war. They considered the latter an insult to their nation’s honor. German Chancellor Philipp Scheidemann even resigned rather than sign the Treaty of Versailles. After much consideration, German Foreign Minister Hermann Mueller and Colonial Minister Johannes Bell travelled to Versailles to sign the postwar agreement on behalf of Germany.

Historians on the Treaty of Versailles

British economist John Maynard Keynes referred to the Treaty of Versailles as a Carthaginian peace (a very brutal peace achieved by completely crushing the enemy) in an attempt to destroy Germany rather than to adhere to the more reasonable principles set out in U.S. President Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points. Keynes believed the sums being asked for reparations were many times more than what Germany could pay. Other historians, chiefly German historian Detlev Peukert, French historian Raymond Cartier and British historian Richard J. Evans disagree with Keynes’ position.

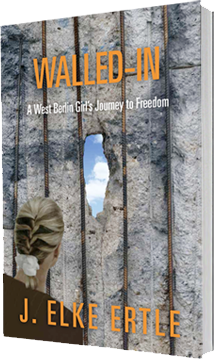

For a sneak peek at the first 20+ pages of my memoir, Walled-In: A West Berlin Girl’s Journey to Freedom, click “Download a free excerpt” on my home page and feel free to follow my blog about anything German: historic and current events, people, places and food.

Walled-In is my story of growing up in Berlin during the Cold War. Juxtaposing the events that engulfed Berlin during the Berlin Blockade, the Berlin Airlift, the Berlin Wall and Kennedy’s Berlin visit with the struggle against my equally insurmountable parental walls, Walled-In is about freedom vs. conformity, conflict vs. harmony, domination vs. submission, loyalty vs. betrayal.