According to census information, almost 50 million German-Americans lived in the United States in 2010. That number represents 16% of the total U.S. population. Not surprisingly therefore, German-Americans are the largest ethnic group living in the United States. http://www.walled-in-berlin.com/j-elke-ertle/hyphenated-americans-german-roots/ At the turn of the last century, New York ranked third in cities being home to the world’s largest German-speaking populations, trailed only by Berlin and Vienna. Entire communities from Wisconsin to Texas consisted almost exclusively of German immigrants and their children. These immigrants founded churches, they established German language newspapers and cultural societies, and they entered politics. But unlike Spanish-Americans, very few German-Americans still master the German language today, and few schools list German as part of their curriculum. Only 1.7% of all German-Americans over the age of 5 even speak the language. Why is that?

Emigrant Memorial (Auswandererdenkmal), Bremerhaven, Germany. The father of these four soon to be German-Americans looks toward the New World. The mother looks back as she leaves the Old Country. Photo © J. Elke Ertle, 2013, www.walled-in-berlin.com

Word War I changed everything for German-Americans

The large number of German-Americans living in the United States lobbied against intervening on the Allies’ side and helped to keep the United States out of World War I for a long time. When the United States finally did enter the war in 1917, German-Americans came under severe, and often violent, scrutiny. Their loyalty was questioned. People with German roots were indiscriminately accused of being spies and double agents. When the Zimmermann telegram was unearthed, a crackpot German plan that proposed Mexico invade the United States, extreme anti-German sentiments took hold and caused lasting damage to German culture in the United States. http://www.walled-in-berlin.com/j-elke-ertle/zimmermann-telegram-wwi-saga-intrigue/

During the 19 month that followed, the German language, German books, newspapers, music, churches, communities, and even German-Americans themselves came under violent attack. Hundreds of German-Americans were interned. More than 30 were killed by vigilantes and anti-German mobs. Hundreds more were beaten or tarred and feathered. The works of Goethe http://www.walled-in-berlin.com/j-elke-ertle/goethe-writes-faust-a-closet-drama/, Schiller http://www.walled-in-berlin.com/j-elke-ertle/friedrich-schiller-champion-of-freedom/, Bach, Mozart and Beethoven http://www.walled-in-berlin.com/j-elke-ertle/ludwig-van-beethoven-lonely-giant/either perished in the flames of public book-burning ceremonies or were relegated to back shelves or basements. Some of the burnings were performed by mobs, others by administrators or officials. For a time, these ceremonies were all the rage in the US, and many German-Americans hid their German roots or changed their names. For book-burning ceremonies in Germany, see http://www.walled-in-berlin.com/j-elke-ertle/empty-bookshelves-book-burning-memorial/

The Immigrants Memorial near Clinton Castle in Battery Park, New York. Clinton Castle served as a processing facility for newly arrived immigrants. Photo © J. Elke Ertle, 2017. www.walled-in-berlin.com

What was left of German-Americans after World War I

In 1910 there were 488 German-language newspapers in the United States with a combined circulation of 3,391,000. Ten years later, there were only 152 publications left with a circulation of 1,311,000. In contrast to the decline of German-language publications, the number of many other ethnic publications increased. Between 1910 and 1920, the number of Spanish-language publications increased from 21 with 74,000 readers to 33 with 256,000 readers. Yiddish publications increased from 8 with 321,000 readers to 23 with 808,000 readers. Italian newspapers went from 28 with 245,00 readers to 40 with 584,000 readers.

My own two cents on the vanishing German-Americans

I am a German-American and speak German, although rarely. The reason is not that I have forgotten how to speak German or that I want to hide my German background, but that few of my friends have German roots. I came to the United States much later than discussed in this article. I came as a young woman during the Cold War and intended to stay for only one year. Born just after WWII, I came from the then walled-in city of Berlin. It was just over twenty years since WWII had ended, and there still was plenty of anti-German sentiment in the United States. But I had expected that. Post-WWII anti-German attitudes were common throughout Europe. There was shame in being German, and we were taught that in German schools.

Born after World War II, my understanding of the war was limited to book knowledge. To avoid detailed discussions on a subject I knew little more about than the rest of the population, I sometimes pretended to be Norwegian. And since I had come to the United States for the purpose of improving my English, I preferred exposure to native English speakers and avoided Germans. Besides, having visited German American clubs occasionally, I found that I had little in common with its members. The non-German members seemed to be in it for the beer, the bratwurst and the polka, and the expatriates, decades my seniors, remembered a Germany that no longer existed. By the time I decided to make the United States my home, most of my friends were non-Germans.

The information presented in this article, aside from “my own two cents,” is based on Erik Kirschbaum’s 2015 book, “Burning Beethoven: The Eradication of German Culture in the United States During World War I.” Eric is a correspondent for the Reuters International News Agency and lives in Berlin, Germany.

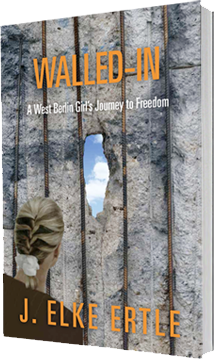

For a sneak peek at the first 20+ pages of my memoir, Walled-In: A West Berlin Girl’s Journey to Freedom, click “Download a free excerpt” on my home page and feel free to follow my blog about anything German: historic and current events, people, places and food.

Walled-In is my story of growing up in Berlin during the Cold War. Juxtaposing the events that engulfed Berlin during the Berlin Blockade, the Berlin Airlift, the Berlin Wall and Kennedy’s Berlin visit with the struggle against my equally insurmountable parental walls, Walled-In is about freedom vs. conformity, conflict vs. harmony, domination vs. submission, loyalty vs. betrayal.